“Don’t wait to buy real estate. Buy real estate and wait.” (Will Rogers)

Spring is in the air and, as the annual uptick in property sales kicks in, let’s address two questions commonly asked by both sellers and buyers who are unsure about exactly what happens after they sign their sale agreement:

- How does the transfer process work?

- How long does it take before the seller gets paid and the buyer becomes the new registered owner?

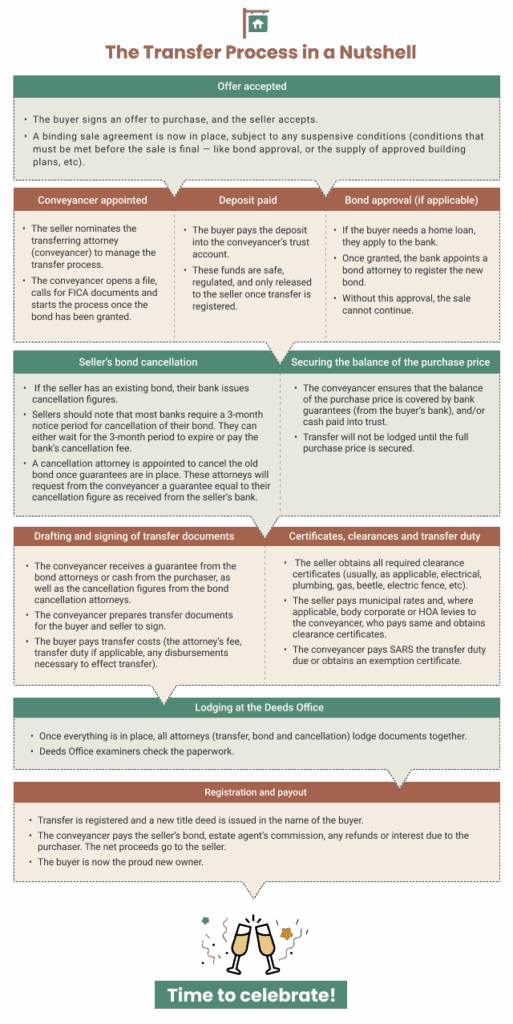

Let’s begin with this simplified “in a nutshell” flowchart of the transfer process

How long does it all take?

How long is a piece of string? If everything goes swimmingly and the bureaucratic stars truly align in your favour, the total timeframe from signing the sale agreement to popping the champagne could be as little as eight weeks. On average, however, it’s safer to work on no less than ten to 12 weeks, and possibly a lot more.

What could delay things? This is a complicated process involving a disparate array of role-players and a host of opportunities for unforeseen delay. Some of the more common sources of delay (and frustration!) centre on bond approval, bank processes, SARS and municipal delays, clearance certificates and repairs, lost title deeds, intervening public holidays, and Deeds Office backlogs. But the list really is endless.

Bottom line: you need professionals in your corner to protect your interests and to move the process along as quickly as possible. We’re here to help!

When Liquidation is Inevitable: A Bad Faith Business Rescue Application Backfires

“If you’re flogging a dead horse, make sure you’re not riding it.” (Josh Stern)

Creditors and company directors alike need to know how best to deal with a company in financial distress. Both should learn to recognise the difference between an enterprise that has failed beyond resuscitation, and one that, given a chance, can be returned to solvency and success.

With that in mind, the law provides you with two main options:

- Liquidation: Liquidation is the winding up of a company that cannot pay its debts. A liquidator is appointed to sell all the assets and to distribute the proceeds to creditors in their order of legal preference. When the business is hopelessly insolvent and has no reasonable chance of recovery, it ensures an orderly closure and fair distribution to creditors. There’s seldom a good outcome for creditors, especially “concurrent creditors” (holding no security or preference) who can generally consider themselves lucky to recover anything more than a few cents in the rand on their claims. Moreover, at the end of the winding-up, the company ceases to exist and is lost to all role-players — employees, creditors, suppliers, the taxman and indeed the economy as a whole.

- Business rescue: This process is designed to rehabilitate distressed companies by protecting them from attack by creditors while a business rescue practitioner (BRP) develops and implements a plan to restructure debts and operations. The idea is to allow the company to continue trading, save as many jobs as possible, and provide a better return to creditors than liquidation would. Critically, however, there must be a realistic prospect of turning the business around and saving the company. If there isn’t, as we shall see below, applying for business rescue can land the applicants in some very hot water.

The dodging debtor and the creditor’s lament

There’s nothing worse for a creditor: after chasing a recalcitrant debtor from pillar to post and finally cornering them, you’re stymied at the last hurdle by the director’s last-ditch application for business rescue.

“Tough”, the director tells you. “That’s the end of your hunt for payment.” When your blood pressure has dropped a bit, you take legal advice — can this really be correct?

In most cases, yes, you are stuck with waiting while a BRP is appointed and a rescue plan formulated and put to you and other role players for consideration. If the application is genuine, you might even recover something worthwhile. At best you could also retain a long-term customer.

But if this is just another debt-dodging or delaying exercise, our courts will come to your rescue. A recent High Court decision not only set aside business rescue proceedings launched in bad faith but also penalised those responsible by hitting them in their own pockets — hard.

A bad faith application backfires, badly

A property-owning company, in a settlement agreement made an order of court, agreed to a creditor selling its property and keeping the proceeds in full and final settlement of its claim. An auction sale was arranged by the creditor, but on the eve of the sale the director of the property company commenced business rescue proceedings and a BRP was appointed.

The BRP sold the property for R3.4m (to the same buyer who’d offered R3.25m at the auction) and prepared a business rescue plan which was duly adopted. The real fly in the ointment was presumably the fact that the plan included remuneration of over R2.2m for the BRP — a sum grossly disproportionate, said the creditor, to the limited scope of her duties.

Having none of that, the creditor applied to the High Court to set aside the business rescue proceedings. The Court was quick to agree to this request, commenting that the company had no operations, income, or employees. There was no viable business to rescue.

More specifically (emphasis supplied): “The business rescue proceedings were accordingly initiated in bad faith, amounting to an abuse of process … the BRP was remunerated extensively without a proper accounting … no reasonable prospect of rescue existed, procedural requirements were ignored, and it is just and equitable to set the resolution aside.”

Punitive costs and a R2.2m fee down the tubes

No wonder, then, that the Court expressed its displeasure at the actions of both the director and the BRP by ordering them to personally pay all costs (jointly with the company itself, for what that’s worth) on the punitive attorney and client scale (much higher and more severe than the normal costs scale). The BRP, in particular, must be mourning the additional loss of her R2.2m fee.

The bottom line

As a creditor, don’t take it lying down if a company tries to dodge or delay paying you through a misuse of the business rescue procedure.

As a director or BRP, be careful never to be seen to abuse the process. It’s not a “get out of jail free” card to delay liquidation or to relieve creditor pressure. As the Supreme Court of Appeal has put it: “Business rescue proceedings are aimed at restoring a company to solvency, and are not to be abused by a company with no prospects of being rescued but mainly to avoid a winding-up or to obtain some respite from creditors.”

The rules and process relating to business rescue and liquidation can be complex, but we’re here to help you navigate them if needed.

Divorce Lawfare: The Serial Litigant and his Stalingrad Strategy

“This [the Stalingrad Strategy] is a strategy of wearing down the plaintiff by tenaciously fighting anything the plaintiff presents by whatever means possible and appealing every ruling favourable to the plaintiff. Here, the defendant does not present a meritorious case. This tactic or strategy is named for the Russian city besieged by the Germans in World War II.” (Judges Matter website)

Divorce disputes are of course intensely personal and emotionally charged affairs — and when feelings run high the resultant fallout can mean protracted, bitter, and costly litigation.

If you are being subjected to a barrage of such litigation, take heart. In balancing our constitutional right to access the courts against the need to prevent people from abusing court processes with endless and meritless litigation, our law provides for “vexatious litigants” to be stopped dead in their tracks.

A recent pair of High Court decisions (featuring the same parties and the same divorce dispute, but in two different battles) provides a textbook example.

A saga of litigation, complaints, threats, and blackmail

This 11-year saga dates from the start of divorce proceedings in 2014, with the financial aspects of the divorce being finalised only in 2020. The ex-wife was awarded a total of R16.8m in accrual, maintenance, and costs. The ex-husband’s property-owning trust was held to be his alter ego, and that opened the door for the house held by the trust (a valuable property in an upmarket Cape Town golf estate) to be sold as his asset.

He responded with a concerted campaign of unrelenting litigation, complaints, and threats — all aimed, the Courts have now determined, at overturning the divorce order.

The list of his serial litigation and intimidation tactics is both long and extraordinary, but suffice it to say that a flood of applications of all sorts to a wide variety of courts (all the way up to the Constitutional Court) is just the tip of the iceberg. He has also lodged professional complaints against all the attorneys and advocates involved in this matter (including his own legal team) and against the Divorce Court Judge. Not even his own financial expert escaped a formal complaint. Allegations of perjury, fraud and collusion abound. He has threatened massive lawsuits (for R210m and R190m to date) against various legal representatives. He was even found to have resorted to blackmail.

Neither his singular failure to reap anything but defeat from any of these endeavours (barring a few minor skirmish successes, and noting that some of the more recent matters remain pending), nor the slew of costs orders made against him (at least one of them on the punitive attorney and client scale), seem to have deterred him in the slightest.

His latest rearguard action, a failed attempt to postpone the auction sale of his house, has earned him yet another defeat and another costs order, with the cherry on top being his being declared a “vexatious litigant”. He can now no longer launch legal proceedings without specific High Court authority to do so.

All’s fair in love and lawfare? Not so fast

As the Court put it: “A fundamental doctrine in our law is, there must be an end to litigation … nobody should be permitted to harass another with second litigation on the same subject as such litigation can be viewed as an abuse of process.” Our courts accordingly have the power to declare such a person a “vexatious litigant”, thus restricting them from launching any new legal proceedings without specific court authority.

To have your opponent declared vexatious, you will need to prove that the person “has persistently and without any reasonable ground instituted legal proceedings in any court or in any inferior court, whether against the same person or against different persons.” There are two legs to that, and note that you can’t stop anyone from pursuing normal appeal and review processes — there must be some abuse of judicial process.

You may also be able to get an order that your opponent provide security for your costs. Although, in this particular matter, the ex-wife was unable to convince the Court to grant her such an order.

Don’t Let Cybercriminals Haunt You this Halloween — Verify, Verify, Verify!“If you suspect deceit, hit delete!” (Online cybersecurity slogan)

October is Cybersecurity Awareness Month, a good time to note that as cybercrime continues to grow, more and more businesses and individuals are falling victim to the dreaded “BEC” or “Business Email Compromise” fraud.

The million-dollar question: Who takes the hit?

Typically in a BEC fraud, email or other electronic communications between a creditor and debtor (often a seller and buyer, or service provider and client) are hacked by criminals, who con the debtor into paying what they owe into the fraudster’s bank account. By the time the parties realise they’ve been had, the criminals are long gone, and all that remains is the million-dollar (sometimes quite literally!) question: “Which one of us takes the hit?”

Until now we have been faced with conflicting High Court decisions on this point, but now the SCA (Supreme Court of Appeal) has settled it: The risk is the debtor’s.

A car dealership must pay twice over

It was a classic case of BEC: A dealership bought two Hyundai Nissan NP200 vehicles from another dealership for R145,000 each. The seller issued invoices showing its banking details. The buyer paid by EFT and sent proof of payment to the seller, which happily (without checking that the funds had actually landed in its account) delivered the vehicles to the buyer.

As always with these cases, one can imagine the sinking feeling that greeted the parties’ realisation that the seller’s emails and the attached invoices had been intercepted, and the banking details subtly altered. As a result, the buyer had paid the full R290,000 to the criminals’ bank account.

Long story short, a real seesaw of a legal battle ensued. The buyer said, “I’ve already paid you”. The seller retorted, “No you haven’t, you paid the criminals,” and sued the buyer for the R290k. The seller won in the Regional Court, lost on appeal to the High Court, but then turned the tables again and celebrated victory in a further appeal to the SCA.

Verify, verify, verify

The SCA’s findings amount to this:

- The onus is always on you as buyer to prove, on a balance of probabilities (i.e. more likely than not), that you have paid the seller.

- When you pay by EFT, you must show that the seller actually got the money. In other words, that you paid into the correct bank account.

- Creditors (recipients) have no legal duty to protect debtors (payers) from the possibility of their accounts being hacked where the debtor could have taken steps to protect itself but failed to do so.

- The obligation therefore is on you as debtor to ensure that the bank account details in the invoice are in fact correct and verified because “it is the debtor’s duty to seek out his creditor”. Fail to follow basic verification steps, and your payment to the wrong account does not remove your liability to pay the debt — you still have to pay your creditor.

Bottom line, the buyer in this case should have verified the banking details given in the emailed invoices before paying. It didn’t, so it couldn’t prove that it had paid into an account authorised by the seller.

It must pay the seller the R290k, with interest and doubtless substantial legal costs.

Don’t make the same mistake

These scams grow more sophisticated by the day, fuelled now by AI-perfected deep fakes, cloned websites and social engineering. Treat all emails, all electronic messages, and all electronic invoices with great suspicion — even if they appear to come from businesses you have known and trusted for decades. Verify bank account details (preferably by speaking to the creditor directly on a number you know to be correct) before paying a cent.

Property sales are particularly vulnerable

Be especially vigilant when buying or selling property because these high-value sales are a particular focus for cybercriminals worldwide. There are rich pickings in the offing, and the opportunities for baddies to intercept and falsify emails is multiplied by the range of trusted role players involved — typically several sets of attorneys, estate agents, and banks as well as the buyers and sellers themselves.

A final note on online security

Let’s end off with a note to everyone: Keep reminding your whole team (not just your accounts department) that securing your computer and email systems against bad-actor compromise is no longer a nice-to-have, it’s essential. This whole unhappy saga could all have been avoided if everyone involved had followed basic security protocols. Prevention is always better than cure.

Give us a call if you need any help.

Legal Speak Made Easy

“Abuse of Process”

“Abuse of process” is the use of our court system to improperly delay, harass, or obstruct another party. Some examples: repeatedly litigating on the same matter without justification, launching meritless cases for ulterior motives, taking unnecessary legal steps purely to frustrate the other side, or dishonestly using a legal process merely as a tactic to block or delay lawful action by another party.

To deter such behaviour and keep our legal system fair and efficient, courts can impose punitive costs orders or even declare offenders “vexatious litigants”, thereby limiting their ability to launch further proceedings without court permission.

Author: Tanners and Associates